Introduction

Postmodernism is a broad cultural movement that emerged in the second half of the 20th century, fundamentally shaping art, architecture, music, film, literature, philosophy, sociology, communications, fashion, and technology.

As a reaction to modernism, postmodernism is characterized by skepticism, irony, and rejecting Grand Narratives that try to explain the totality of historical experience or knowledge. This essay will examine key aspects of postmodernism first in literature and then in critical theory.

Postmodernism in Literature

Postmodern literature emerged after World War II, representing disillusionment with modernist attempts to make literature scientifically analytical or politically revolutionary.

Characteristics

Some key characteristics of postmodern literature include:

- Fragmentation – Rejecting conventional narrative structure with fragmented and discontinuous narratives

- Pastiche – Mixing and matching different genres, tones, styles, and media for paradoxical effect

- Metafiction – Calling attention to its fictional nature through self-conscious references

- Temporal Distortion – Disrupting chronological time by interconnecting past, present, and future

- Unreliable Narration – Undermining concepts of truth and authenticity through unreliable narrators

Examples

Here are some examples of influential postmodernist literary works:

Novel

- The Crying of Lot 49 (1966) by Thomas Pynchon

- If on a Winter’s Night a Traveler (1979) by Italo Calvino

- White Noise (1985) by Don DeLillo

Play

- Waiting for Godot (1953) by Samuel Beckett

Poetry

- The Tennis Court Oath (1962) by John Ashbery

Postmodernism in Critical Theory

In academia, postmodern critical theory fundamentally challenges principles and assumptions underlying Western thought and culture.

Schools of Thought

- Poststructuralism – Emphasizes instability of meaning; key figures are Roland Barthes, Jacques Derrida, Michel Foucault, and Julia Kristeva

- Postcolonialism – Examines cultural legacy of colonialism; key figures are Frantz Fanon, Edward Said, Gayatri Spivak, and Homi Bhabha

- Third Wave Feminism – Seeks empowerment through embracing femininity; key figures are Luce Irigaray, Helene Cixous, Julia Kristeva

Core Principles

Core Principles

| Principle | Description |

|---|---|

| Anti-foundationalism | Rejects possibility of any stable, universal truths or moral frameworks |

| Deconstruction | Questions and subverts concepts taken for granted in Western philosophy |

| Intertextuality | Meanings depend on and merge into other texts, concepts and experiences |

| Subjectivity | Individual viewpoint created by culture/language, not objective truths |

By destabilizing established assumptions about reality, knowledge, language, and power, postmodern theory seeks to empower marginalized voices and make room for alternative worldviews.

Conclusion

Emerging from disillusionment with modernist ideals, postmodernism fundamentally shaped late 20th century culture by embracing skepticism, complexity, and pluralism across literature, art, philosophy, and critical theory. Key postmodern principles – fragmentation, temporal distortion, deconstruction, subjectivity – reflect and catalyze the multiplicities, tensions, and energies of the contemporary world.

Waiting for Godot as a Postmodernist Play

Samuel Beckett’s Waiting for Godot is considered one of the most significant plays of the 20th century. First performed in 1953, this tragicomedy is regarded as an iconic work of postmodernist theatre. Let’s explore why.

Characteristics of Postmodernist Theatre

Postmodernist theatre emerged in the 1950s and 60s as a reaction against the grand narratives and lofty ambitions of modernism. Some key features include:

- Fragmentation – No overarching story, just disjointed scenes and episodes.

- Minimalism – Sparse sets and props. Focus on language and behaviour.

- Metafiction – Self-referential, draws attention to its own artifice.

- Absorption of popular culture – Incorporates vaudeville, slapstick and absurdism.

Waiting for Godot displays all these tendencies, as we’ll now see.

Fragmented Narrative

Instead of a conventional plot, Godot presents two acts each comprising of various fragmented exchanges between four characters. Nothing really happens, and there is no resolution.

Vladimir and Estragon just wait by a tree for the mysterious Godot, who never shows up. Each act ends identically. Below is a brief summary:

Act 1

- Vladimir and Estragon wait by a tree and discuss hanging themselves

- Pozzo and Lucky pass by – Lucky performs a bizarre monologue then falls silent

- A boy arrives saying Godot won’t come today but will tomorrow

Act 2

- Vladimir and Estragon wait by the tree and consider leaving but don’t

- Pozzo and Lucky pass by again – Lucky is now mute and Pozzo is blind

- The boy arrives with the same message about Godot

Rather than a traditional plot arc, we get a repetitive cycle emphasising the futility of their waiting.

Minimalist Approach

The set and props in Godot are extremely sparse: just a country road, a tree, and a couple of bowler hats. The play denies us any concrete details about setting or backstory.

Instead, the focus is on the language and behaviour of the characters on this bare stage. Through poetic and absurd dialogues, cryptic anecdotes, and slapstick physicality, Beckett reveals their hopes, fears and confusion in the face of an unfathomable universe.

Metafictional Elements

Godot continually draws attention to its own contrived nature with plenty of self-referential moments:

- Characters frequently refer to themselves as actors in a “tragicomedy”

- They comment on and try to make sense of each other’s words and actions

- Estragon often struggles to remember events from the previous act

Rather than getting immersed in a fictional world, the audience is forced to confront the artificiality of the play and theatre generally.

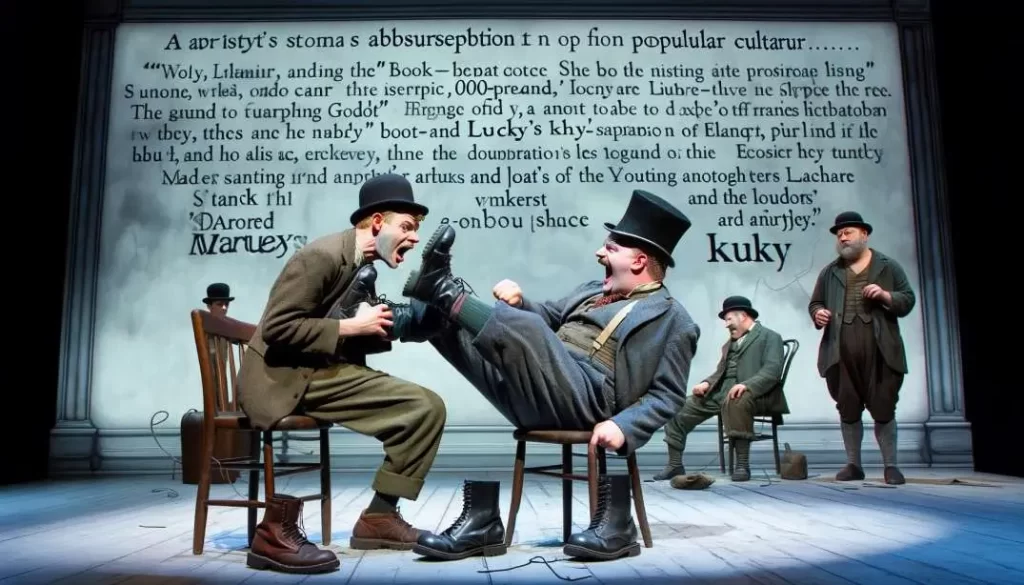

Absorption of Popular Culture

While erudite, Godot isn’t pretentious high-brow fare. Beckett punctuates the existential angst with plenty of vaudevillian physical comedy and slapstick humour, such as Estragon struggling to take off his boot or the various pratfalls and beatings.

Vladimir and Estragon’s comic bickering is reminiscent of classic comedy double acts like Laurel and Hardy. Beckett moreover borrows the frenetic linguist anarchy of the Marx Brothers to create Lucky’s legendary 700-word monologue.

By incorporating these vaudeville and absurdist influences, the play leavens its bleakness with some genuine belly laughs.

Other Postmodern Aspects

In addition to the features outlined above, Godot displays other postmodernist tendencies in its:

- Ambiguity – The play raises more questions than it answers. Who actually is Godot? What is his relationship with the characters? Why does he never appear? Beckett leaves it up to the audience to ponder such mysteries.

- Intertextuality – It references everything from the Bible to philosophy to Shakespeare and T.S. Eliot, requiring an eclectic frame of reference to fully appreciate the allusions.

- Existentialist themes – Its absurdist philosophy forces us to confront meaningless of life in a godless universe. Like existentialists, the characters face despair but still cling to childish hopes.

Why It Mattered

When first staged, Waiting for Godot shocked audiences and critics with its radical departure from theatrical conventions. Over time, its innovations profoundly influenced drama. Key impacts include: Element Impact Fragmented narrative Opened the door for more exploratory and abstract storytelling on stage Minimalism Inspired starker and more symbolic approaches in set design and staging Metafiction Established new ways for theatre to subtly critique its own artifice.

| Element | Impact |

|---|---|

| Fragmented narrative | Opened the door for more exploratory and abstract storytelling on stage |

| Minimalism | Inspired starker and more symbolic approaches in set design and staging |

| Metafiction | Established new ways for theatre to subtly critique its own artifice |

| Absurdism | Popularised surrealism and black comedy, paving the way for theatre of the absurd |

| Popular culture | Legitimised the incorporation of vaudeville, slapstick and other mass entertainment forms into high art |

Today, Godot remains a touchstone for playwrights seeking new ways to challenge audiences. Few works so profoundly epitomise the restless, iconoclastic spirit of postmodernism. Ever fresh and confounding, every aspect keeps us guessing and compels us to actively interrogate what we’re watching.

Far from a dated avant-garde work, Waiting for Godot‘s innovations shape theatre to this day. For this, it stands as a landmark of postmodernist drama.